THE HISTORY OF THE MAYFLOWER

In her day the Mayflower was an unremarkable little ship, so unremarkable that her details are largely lost to us. What made her of historical importance was her historic trans-Atlantic crossing of 1620, when she carried the Pilgrim Fathers and their families across the then immense barrier of the North Atlantic Ocean. This allowed them to escape religious persecution and to establish an English colony in what would come to be called New England.

Harwich was a thriving and important English port in the 1600s, possessing ship-building yards, ship-owners, sea-captains and seamen, and it is generally thought that the Mayflower was built there sometime before 1600. What is certain is that she was commanded and part-owned by her Master, Captain Christopher Jones, who was among the elite of the town which also produced another remarkable mariner, Christopher Newport. Jones’s house still stands close to the waterfront at Harwich and was clearly the dwelling of a man of substance.

From being a Harwich ship, the Mayflower was later registered at Rotherhithe on the River Thames, possibly due to a change in her owners. At the time it was customary for merchant ships to be owned by a syndicate who bought into the sixty-four shares into which every ship was divided. Because of the high rate of loss, ship-wreck, foundering, war or any other mishap, no-one invested in a single vessel and the inherent risks were thereby spread. A shift in a number of shares could, therefore, change the home-port of a vessel, so the change to Rotherhithe is not particularly significant and, in any case, Christopher Jones remained in command.

Typical of her day, the Mayflower was ‘ship-rigged’, that is to say she had three masts – a fore, main and mizzen – on the forward two of which she carried square sails, with a fore-and-aft lateen sail on the mizzen-mast. She also carried a square ‘sprit-sail’ under her bow-sprit. In the 1600s only two square sails were carried on each mast. The lower on the foremast was called the fore-sail, above which was the fore-topsail; a main-sail and main topsail were carried on the middle or main-mast which was the tallest of the three. Both the fore and main-mast traditionally bore flags, often one of the owning syndicate’s design, but often a national flag such as St George’s cross. The important national ‘ensign’ was ‘worn’ (not flown) at the stern and denoted a ship’s nationality to any stranger. This was important if a state of war existed.

Since a merchant ship earned her living from carrying cargo, her size was denoted by its capacity. This was based upon a long-standing tradition of calibrating the volume of the hull by the number of large barrels of wine that could be stowed in her hold. These were called ‘tuns’ from which we get our modern notion of tonnage, but it is worth noting that the gross and registered tonnage of a ship to this day are not measurements of weight, but of capacity. The Mayflower’s ‘burthen’ was 180 tuns, from which certain assumptions about her size may be made. Around 1600 ship-building was a craft, based on empirical deductions and the individual experience of the master ship-wright in charge. There was no concept of naval architecture, but the success of the English galleon of the late Tudor period influenced the notions of the day. Modern studies of the ship-wright’s art based on a multitude of sources, including archaeological evidence, have led to conclusions enabling the reconstruction of a ship of the period. In addition, many features were standard to ships of all types, all of which helps to reconcile the likely appearance of our reconstruction.

The Protestant emigrants who would gather under the leadership of the Pilgrim Fathers were not wealthy; thanks to their religious beliefs most had already abandoned their homes in England to live at Leyden in The Netherlands. To finance the voyage a syndicate was formed, the actual emigrants being counted as a single share-holder at £10 per head. After numerous difficulties and delays the original families embarked in the Speedwell at Delft, which was joined at Southampton by others in the Mayflower which had departed from Rotherhithe.

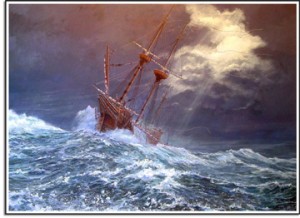

When some 200 miles clear of the land, it was found that the Speedwell leaked excessively and the two ships put back into Plymouth where the Speedwell was deemed unfit to continue the voyage. It was therefore left to Jones and his crew to take on victuals and water and embark some of the Speedwell’s passengers. Accordingly the deeply-laden Mayflower sailed from Plymouth in September 1620 with about 120 souls aboard. She was bound for the coast of Delaware in the least propitious season of the year, autumn gales being frequent in the North Atlantic.

After a sixty-six day passage during which an estimated two of the emigrants perished during the journey, Jones made the land 400 miles north of the Delaware River, anchoring off Cape Cod on 19 November 1620, near modern Provincetown. Realising they were not where they intended to be owing to the contemporary difficulties in navigation, the Pilgrim Fathers bowed to the workings of providence and decided to establish their colony in the vicinity of their landfall and selected a site. There being no concept of female suffrage, the men took it upon themselves to draw-up a document establishing the means by which they would govern themselves. Having all subscribed to this, known as the Mayflower Compact, a landing was finally made on 16 December at the selected spot where what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts, was founded.

More deaths occurred during the winter that followed. Conditions were harsh, the emigrants’ immune systems were probably depressed from the salt food and cramped conditions they had endured during their voyage, and they found their preparations for establishing themselves were inadequate. Much as they must have wished to leave the Mayflower, the survivors probably owed their lives to Christopher Jones’s insistence on standing-by the colonists and providing some measure of support until they had built shelters. He would also wish to ensure that the health of his crew had recovered enough to make the return voyage to England which he undertook in April 1621.

Despite their privations the surviving emigrants established their settlement and began the English colonisation of North America. As for the Mayflower herself, she fades into history as mysteriously as she emerged. Christopher Jones died in 1622 and his old ship, the Mayflower, was broken-up at Rotherhithe the following year. Many of her timbers were probably salvaged and used in the construction of cheap, Thames-side houses. This form of recycling was common at the time and many of the old, timber-framed houses in Harwich show the signs of utilising ship’s timbers to this day – an echo of the past and of the significance of obscure ships like the Mayflower.

Although no material trace of her remains, the legacy of the Mayflower, her Master, crew and passengers, is immortal, for it is the triumph of human courage in the face of adversity. Confronting religious persecution in Europe, the first emigrants to America took on the challenge of the North Atlantic with the help of doughty English mariners, to establish a colony in what would, in due course become, the United States of America.

Historical Associate Captain Richard Woodman LVO FRHistS FNI